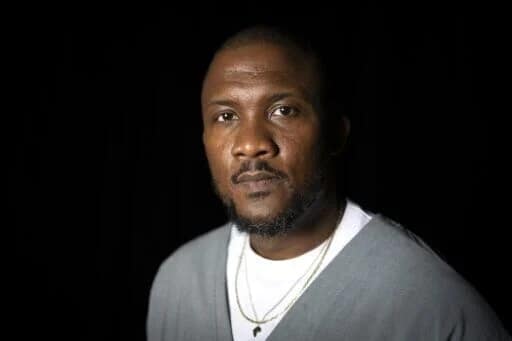

Wale Davies is not in a hurry when he talks about himself. He knows the weight of memory, how easily it slips through fingers, how often it bends to myth. For most of his career, audiences have known him as Tec, one half of the Lagos rap duo Show Dem Camp, whose albums have carried the warmth of palm-wine guitars and the coolness of late-night confession. But in recent years, another Wale has been making himself known—one who is less interested in the intoxication of rhythm than in the shadows that linger behind it.

That shadow is, quite literally, his father’s. Wale was only four when his father died, leaving behind fragments: a scent, a voice, a silhouette half-remembered in family stories. His younger brother, the filmmaker Akinola Davies Jr., was even younger—barely old enough to hold a coherent memory at all. For decades, the brothers circled around this absence, speaking about it occasionally, but never fully confronting it. Art became their way of returning to the wound. For Wale, music offered a vocabulary of loss and belonging. For Akinola, cinema provided a canvas on which memory could be reconstructed.

Their collaboration, My Father’s Shadow, is the convergence of those paths. The film, which premiered at Cannes in 2025, is set in Lagos in 1993, a moment when the country seemed on the verge of something different. The June 12 election, which promised a democratic renewal, collapsed in betrayal, leaving Nigeria suspended in a haze of hope and anger. Against this backdrop, the film imagines two brothers spending a day with their estranged father. It is both personal and political, a story of intimacy folded into the larger story of a nation in turmoil.

Wale first began writing the script in 2012, sketching out fragments of dialogue, revisiting family lore, and teasing apart what was true from what might have been imagined. He knew he was trying to reclaim something that could never fully be recovered. “The father in the film is a ghost,” he said in an interview. “But he is also a metaphor—for sacrifice, for absence, for the way Nigerian fathers were often forced to choose between being present and providing.” In that sense, the story became bigger than his family. It became a way of understanding a generation of men and the children they left in their wake.

If Show Dem Camp made Davies into a public figure, My Father’s Shadow has made him into something else: a custodian of memory. The film is not just a portrait of grief; it is also a meditation on how history and politics intrude on the private sphere, how a household can mirror the disillusionment of a nation. The brothers’ father, though absent, is cast as a man caught between impossible responsibilities—a stand-in for the country itself.

The film’s reception has already entered the record books. It was the first Nigerian film to appear in Cannes’ official Un Certain Regard selection, and it left the festival with a Caméra d’Or Special Mention. But for Wale, the recognition is less important than the reclamation. He has always been aware that art can be fleeting, consumed quickly, shuffled into playlists or streaming queues. What he and his brother have made is harder to discard. It asks its audience to sit with ambiguity, to acknowledge that the past is always partial, always layered with imagination.

Back in Lagos, Davies still records and performs, still embodies the cool, thoughtful presence that has made Show Dem Camp a cornerstone of Nigerian hip-hop. Yet even there, his verses carry the resonance of someone preoccupied with memory. The beats are lighter, but the shadows remain. In a way, My Father’s Shadow is simply the latest iteration of a lifelong project: telling stories about what it means to live in the gap between what is promised and what is lost.

Wale Davies is who he thinks he is—a son, a rapper, a writer, a witness. He is not merely performing identity, but insisting upon it. In the music, in the film, in the act of remembering, he keeps circling back to the same point: that absence shapes us as much as presence, and that in telling the story of what we lacked, we may finally come closer to who we are.