The 10th edition of The Platform welcomed acclaimed speculative fiction writer Erhu Kome, an Urhobo author renowned for her dynamic fantasy narratives and her distinction as the premier female Nigerian author of bizarro fiction. The conversation, themed on Indie Publishing and Storytelling, offered a candid look into the mechanics, motivations, and mindset required to thrive in Nigeria’s literary landscape as an independent author.

Kome, whose debut YA fantasy novel The Smoke That Thunders garnered international acclaim, spoke plainly about the necessity of taking control of one’s narrative, both on the page and in the market. In a creative landscape often obsessed with metrics and speed, Kome explored what it means to write with intention—and how stories become vessels for identity, memory, and possibility.

The Desire for Delight: Writing Beyond Trauma

In discussing the genesis of her writing career, Kome revealed an inspirational origin story rooted not in grand literary tradition, but in the pure joy of popular fiction. She attributes her initial drive to write to reading Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight, a book that sparked a realisation: she could write entertaining, large-scale speculative stories with Nigerian characters.

This pursuit of entertainment forms the core of her storytelling philosophy. While acknowledging the importance of addressing heavy themes, Kome stated that her primary motivation is to write what she enjoys consuming, often citing titles like Lord of the Rings.

“My main focus is to entertain, to make it fun,” she noted. “I think there are so many Nigerian authors that focus on the trauma, which is fine, but I like the fun part, I love the magical things.”

Her love for fantasy and magical realism—stories rooted in West African mythology—is a deliberate choice to provide readers with an escape and a sense of wonder, challenging the notion that African literature must exclusively serve as a vessel for pain or social commentary. She believes fantasy is not mere diversion—it’s a way to amplify what realism sometimes cannot hold.

“My worlds often live in tension,” she reflected. “They are places where gods, or spirits, or declines interact with human choices. And in that, everyday questions—identity, justice, inheritance—become urgent.”

Slowness in Writing: The Craft Resisting Output

One of the discussion’s recurring motifs was slowness—a pushback against deadlines, algorithms, and the tyranny of output. Kome described her writing process not as linear but layered: drafts, pauses, re-reads, letting things sit, returning with fresh eyes. She contrasted this with pressures she sees in social media-driven writing cultures, arguing that slowing down allows space for revision and depth.

“If you never step back, you won’t hear what your story is trying to whisper,” she said. “A character might shift. A metaphor might emerge late. Patience sometimes reveals what urgency hides.”

While acknowledging that fast content creation, newsletters, and podcasting all have their place, she stressed that the core of craft must resist being entirely subsumed by them.

Identity, Language, and Specificity

Kome, a writer rooted in Urhobo heritage and raised in Benin City, weaves speculative fiction with deep cultural threads. The discussion shifted to who gets to tell stories, a subject near to Kome’s convictions. She spoke of writing from an Urhobo-rooted lens not as essentialism but as reclamation. In many African literary spaces, she observed, myths and cosmologies are often exoticised or subsumed into a pan-African “mystical” stereotype. What she strives for is specificity.

While much of her work is in English, she often incorporates vernacular, idiomatic drift, or cultural rhythm—not as ornamentation but as narrative gravity. When asked about the tension of accessibility for both local and foreign readers, Kome responded that the tension is inevitable. She wrote first for herself and those who share her perspective, and then for those who don’t, operating on the hope that curiosity and empathy will catch up.

The Reality of the Independent Hustle

Having navigated both the traditional and independent routes, Kome offered a clear-eyed comparison of the two publishing paths. She outlined the trade-off between control and convenience:

- Traditional Publishing: Offers ease of process, where the author largely focuses on editing and a portion of the marketing. The publisher manages the cover, formatting, and distribution, with the author often receiving an advance upfront.

- Indie Publishing: Demands that the author is the publisher, meaning they must source and manage everything: hiring designers, editors, formatting specialists, planning the marketing, and handling distribution. This path requires significant upfront time, effort, and financial investment, with “money leaving your pocket” before returns.

Despite the heavy workload and administrative challenges—such as the complexities of obtaining a Nigerian ISBN and the high costs of local printers—Kome expressed a strong preference for the independent route, due to the complete control it affords over the final product and artistic vision.

Elevating the Nigerian Indie Standard

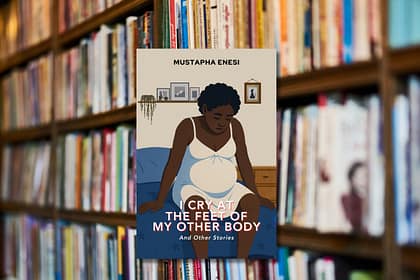

A central message of the discussion was Kome’s mission to professionalise and elevate the perception of Nigerian indie literature. She is determined to dispel the international misconception that self-published works are inherently “not good” or “poorly edited.”

Kome’s approach to indie publishing is characterised by a commitment to quality and reader appreciation. She strives to give her Nigerian readership the same high-quality aesthetic experience enjoyed by international book consumers, referencing the global culture of custom campaigns and beautiful packaging.

“I wanted Nigerian readers to have an ‘abroad experience’ [with books]—the nice-looking books, the PR boxes, as a way of appreciating their support,” she stated.

For Erhu Kome, indie publishing is not a fallback option, but a powerful, intentional platform to maintain artistic control and deliver high-quality speculative fiction.

The Rights Debate and Ownership

At one juncture, the conversation turned to the thorny terrain of publishing rights. Kome revealed that she has been engaged in a protracted effort to reclaim rights to her earlier work, Not Seeing Is A Flower, originally published by a U.S. press. Her reflections were candid, recounting silence from the publisher, missed royalty payments, and the emotional toll of having one’s intellectual work handled poorly.

Her counsel to emerging writers was firm:

“Never sign anything you don’t fully understand. Try to get an agent. Retain clarity on what remains yours.”

She urged writers not to surrender control too early, nor to assume that publishing prestige absolves the need to safeguard one’s own voice and intellectual property.

Conversations Between Art Forms

In The Platform’s spirit of interdisciplinarity, Kome was asked how writing dialogues work with other art forms. She welcomed this question with enthusiasm, stating that narrative doesn’t live alone—it resonates with music, visual art, performance, even scent and space.

She shared a moment when a visit to a gallery installation mid-draft—the lighting, the texture of the walls, the silence in the room—seeped directly into the next scene she wrote. She encouraged fellow creatives to cross-pollinate: read painters, watch theatre, step into soundscapes. The architectures of meaning, she said, are richer that way.

A Call for Creative Liberty and Collective Care

Towards the end, Kome affirmed that spaces like The Platform—public, intimate, conversational—are vital. They are places to fail, to surface doubt, to hear and be heard.

She expressed a hope that The Platform will continue to build intergenerational bridges—connecting writers, readers, and artists—to foster “creative liberty, collective care, and radical kindness” as modes of growth.

In an era when culture often incentivises speed and constant output, the conversation with Erhu Kome reminded the audience that creativity demands patience, that stories are conduits of identity and possibility, and that writers—especially those writing from margins—must guard their sovereignty even as they open themselves to new audiences. She calls not for retreat, but for a recalibration: to slow, to listen, and to build with intention.